August

2019

HYDROCARBON

ENGINEERING

18

Table 1 presents a summary of Australia’s LNG projects, as

reported by the Department of Industry, Innovation, and

Science.

According to the Australian Department of the

Environment and Energy, national LNG exports in financial

year (FY) 2017 – 2018 totalled nearly 61.691 million t valued at

over AUS$30.9 billion. Japan was the largest customer,

importing 27.422 million t, followed by China, which

purchased 19.644 million t, and South Korea, which imported

6.028 million t. The Department noted that new customers

have emerged, including small markets of New Caledonia and

Timor-Leste.

Australia’s LNG exports have soared, and they are reaching

a larger number of customers. Figure 3 shows the growth and

diversification of exports from 1997 through 2018. Japan is the

single-largest customer, but exports to other Asian customers

have grown significantly. In the early years, Japan took

essentially all (more than 95%) of Australia’s output, with

occasional cargoes going to the US or Europe (Spain and the

UK.) South Korea received its first cargo in 2000, and exports to

South Korea rose to 10.8 billion m

3

in 2018. Taiwan and India

both started purchasing Australian LNG in 2005. Taiwan

imported 3.5 billion m

3

in 2018, while India imported

2 billion m

3

. China received its first cargo of Australian LNG in

2006, and China has emerged as a major consumer. Exports to

China jumped from a modest 1 billion m

3

in 2006 to

32.1 billion m

3

in 2018 – nearly as much as Japan imported.

Australian oil product demand

Australia’s domestic sales of petroleum products have grown

at a robust rate of 2.2% per year on average between

FY 2010 – 2011 and 2017 – 2018. Demand grew from

893 600 bpd in 2010 – 2011 to over 1.041 million bpd in

2017 – 2018. Diesel and jet fuel have posted the most rapid

growth. The demand barrel is high in value, with the

percentage share of fuel oil and other products falling from

6.1% in 2007 – 2008 to 3.3% in 2014 – 2015. Fuel oil demand fell

from 27 000 bpd in 2007 – 2008 to 12 400 bpd in 2012 – 2013,

but it crept back up to 16 900 bpd in 2016 – 2017. This may in

part be explained by the declining price of oil, the

introduction of Australia’s carbon tax in 2012, and its repeal in

2014, as discussed.

Australia’s gasoline demand fell from 331 500 bpd in

2007 – 2008 to 312 100 bpd in 2014 – 2015. It crept back up

to 316 500 bpd in 2017 – 2018. The market is growing

more oriented toward diesel, demand for which grew

from 314 800 bpd in 2007 – 2008 to 486 800 bpd in

2017 – 2018. Gasoline’s share of the demand barrel fell

from 37.8% in 2007 – 2008 to 30.4% in 2017 – 2018,

while diesel’s share has risen from 35.9% in 2007 – 2008

to 46.8% in 2017 – 2018. Jet fuel demand also has grown

quickly, with demand rising from 108 600 bpd in

2007 – 2008 to 161 600 bpd in 2017 – 2018.

Ethanol blended gasolines of up to 10% ethanol by

volume began to be phased in beginning in 2006. The

State of New South Wales was the first to institute a

blending mandate, and Queensland followed. The

mandates are limited in scope and area, and biofuels

have had to compete with inexpensive oil over the past

few years. Sales of ethanol blended gasoline jumped to

57 900 bpd in FY 2010 – 2011, but sales languished, and they

averaged just 40 300 bpd in 2014 – 2015. An uptick in

demand to 44 500 bpd came in FY 2017 – 2018 as additional

ethanol blended gasoline was required in Queensland. A

steady upward trend would require additional blending

mandates and/or more favourable economics.

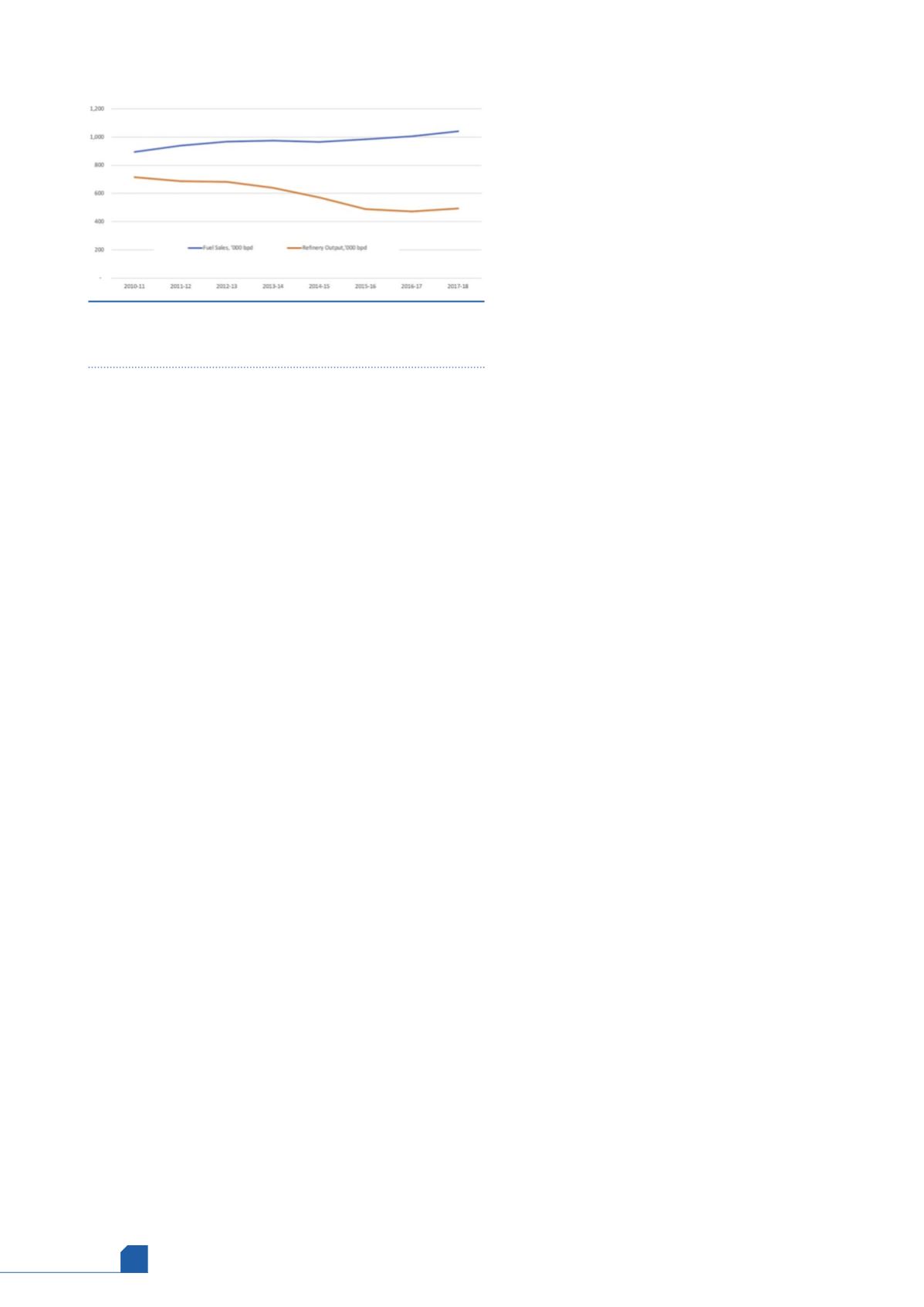

Australian fuel demand has grown, yet refinery output

has fallen. Figure 4 compares the trend in demand with

refinery production. In 2010 – 2011, fuel sales exceeded

refinery output by 178 000 bpd. In FY 2017 – 2018, the supply

gap had tripled, with fuel sales exceeding refinery

production by 547 000 bpd. The following section discusses

the contraction of Australia’s refining sector.

Australian refining: plans for

expansion turn to contraction

The 1980s and 1990s were known as the time of the Asian

demand boom. By the mid- to late-1980s, oil prices had

collapsed, and demand began to grow in some Asian

countries at double-digit rates. Essentially every country in

the region expanded its refining industry during that time.

Australian refinery capacity expanded also. For a time,

Australian refining companies and potential new entrants

explored the idea of building export-oriented refineries

targeted at the growing Asia-Pacific market. These ideas

included proposals to build sophisticated grassroots

refineries in the Northern Territory and Western Australia.

These states possessed oil and gas reserves that hitherto

had been less attractive because of their distance from

larger population centres. The Asian Boom provided more

incentive to develop Western Australian basins, which were

also essential to replace supplies from mature and declining

oilfields in Victoria and South Australia.

But these were not low-cost developments, and

Australia remained a net importer of refinery feedstock.

Building export refineries would therefore have relied upon

imported feedstock, likely shipped in from the Middle East,

and product then would be shipped into Asia, where it

would have had to compete with other exporters, including

Singapore. The economics were not compelling, and

Australian export refinery proposals were postponed and

ultimately cancelled.

Australia’s downstream companies then began to

contemplate the outlook for growth in their existing

Figure 4.

Australia’s refinery output falling below demand

product sales (‘000 bpd). Source: Department of Environment

and Energy.