August

2019

HYDROCARBON

ENGINEERING

14

BP’s Chief Economist, Spencer Dale, observed that some of

the world’s increase in energy demand stemmed from

severe weather – a symptom of global climate change. Thus,

the cycle worsened in 2018. Dale concluded “Last year’s

developments sound yet another warning alarm that the

world is on an unsustainable path.”

1

Australia is in the midst of battling global climate

change, and the country has relatively more to lose if the

battle is lost. The actions taken on this issue will affect the

Australian energy industry more than any other single

factor. This article will discuss Australia’s love-hate

relationship with fossil energy, the challenge of global

climate change, the growth of the LNG industry, the

shrinking of the downstream oil industry, and the impact

this has had on refined product trade.

Fossil dependence and the short-lived

carbon tax

Australia possesses significant reserves of oil, natural gas, and

coal. Developing, using, and trading these fuels contributed

enormously to Australia’s overall economic development and

prosperity in past decades. They also provide for the great

majority of Australia’s energy needs today. Fossil energy

accounts for 92.8% of Australian primary energy. Clearly,

whittling away at this fuel mix is an immense undertaking. Yet

Australia must take steps to reduce its emissions. The

government remains determined to meet its Paris Agreement

target of a 28% reduction in emissions between the 2005

baseline and 2030. But recent developments have placed

Australia even further away from meeting this pledge.

It was clear more than a decade ago that coal and fossil

energy use would have to be cut, and that a carbon tax

would be the logical way to achieve this. The

government, led by the Labor Party, instituted a carbon

tax in July 2012. However, there was not enough

bipartisan support for the tax. The opposition

Liberal-National coalition quickly launched a campaign

with a catchy ‘axe the tax’ slogan, won control of the

government, and repealed the tax in July 2014. Australian

coal consumption, which had been declining for five

years, ratcheted back up in 2015 and 2016. CO

2

emission

also rose in 2014, 2015, and 2016.

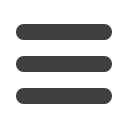

Australia has made some progress on its overwhelming

dependence on fossil energy. As Figure 1 illustrates, fossil

energy dependence was 95% in 1965, and it gently trended

up to a peak of over 97% in the 2007 – 2009 period. Coal

use hit an all-time high in 2008, which was the year that

oil prices spiked, making domestic coal even more

economically attractive. Oil prices collapsed in 2009, and

oil demand began to rise. During the decade from

2008 – 2018, BP reports that Australian oil demand rose at

1.7% per year, natural gas use rose at 3.8% per year, and

alternatives and renewables use grew at 11.5% per year.

Coal use shrank at a rate of 2.7% per year.

Coal’s downward path has been bumpy, however. Coal

demand fell in the years leading to the carbon tax, then

edged back up when the tax was repealed. According to

the Department of Environment and Energy, coal use in

the electric power sector fell for five years in a row from

2008 – 2009 to 2013 – 2014 before rising again in

2014 – 2015 and 2015 – 2016. Despite this small recovery, coal’s

share of electric power generation shrank at a rate of 1.5% per

year on average during the decade from 2007 – 2008 to

2017 – 2018. The share of renewables expanded at a rate of

8.3% during that time, led by hydro, wind, and solar power.

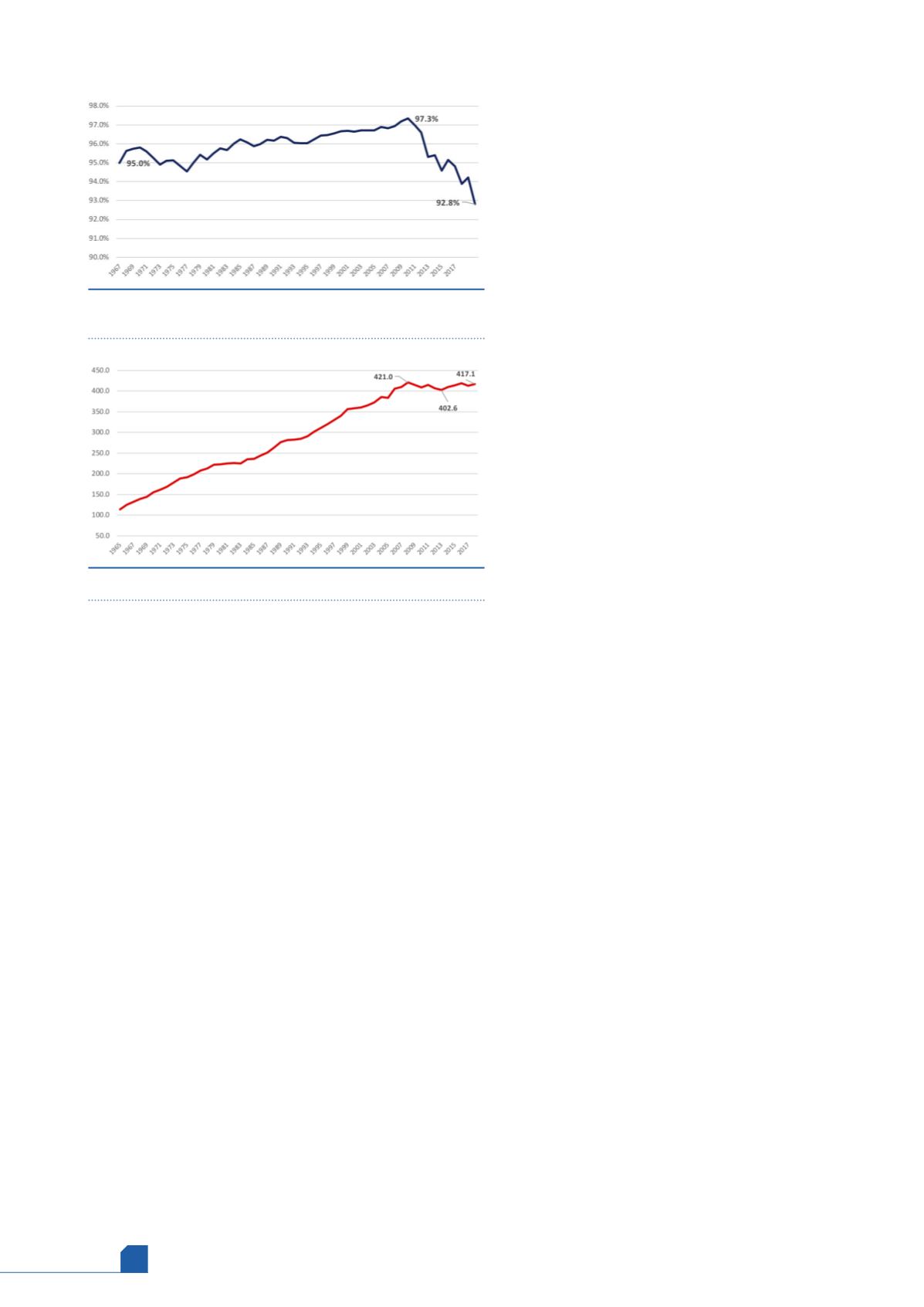

Unsurprisingly, Australia’s CO

2

emissions also rose as fossil

energy use increased. The 2008 peak in coal use

corresponded with a peak of 421 million t of CO

2

emissions,

as shown in Figure 2. Government actions including the

carbon tax helped flatten the upward trend in carbon

emissions. CO

2

emissions fell to 402.6 million t in 2013. The

carbon tax was repealed in 2014, and CO

2

emissions crept

back up to 417.1 million t in 2018.

The debate continues over how much should be spent,

and by whom, to protect the environment. The carbon

intensity of coal, for example, is approximately twice that of

natural gas, but Australia has a massive coal industry.

Australia is the world’s largest exporter of coal, with exports

in 2018 valued at US$47 billion. Many coal deposits are

located close to consumers, and favourable transport

economics channel coal into the domestic market. Coal is

considered a low-cost source of energy, and it accounted for

30.8% of Australia’s energy mix in 2018. This level has been

cut significantly, from 44.3% a decade earlier in 2008. Still, it

remains one of the highest percentages in OECD, exceeded

only by the Czech Republic and Poland, who joined the

OECD in the mid-1990s.

According to the Australian government, the country’s

resources and energy sector accounted for 8.8% of Australian

GDP in 2018.

2

These commodities include iron ore, LNG, coal

and metals. This economic sector represented 57% of goods

exports in 2018 and provided 250 000 jobs.

Figure 2.

Australia CO

2

emissions (million t). Source: BP.

Figure 1.

Australia primary energy consumption (% fossil).

Source: BP.