July

2020

HYDROCARBON

ENGINEERING

60

information freely. These improvements have been facilitated by

new networking technologies, especially the internet and

wireless networks.

The one area that has been reluctant to join the integration

transition is safety. Plant operators and organisations responsible

for writing standards have leaned towards keeping safety

systems minimally integrated, if at all, and far more basic in

functionality. Simplicity is thought to equal reliability, and in

many contexts, this is a good idea, as one wants the

pressure-relief system on a reactor filled with toxic product to

do its job every time.

However, every situation does not call for the highest

degree of separation and isolation, and in many instances,

integration creates a safer system. Moreover, it is possible to

capture data from safety systems without interfering with their

critical functions. This article will look at two examples of

where safety-related functions can be extended and integrated

to improve safety.

Personnel location systems

Plant managers have long wanted a mechanism to determine

who is in the plant and where each individual is at any given

moment. If there is a safety incident, it is important to know

which people might still be in harm’s way, or if they have

moved to safe areas. Implementing this type of system has

seen many barriers due to cost, design, and installation

investments required.

Location systems indicating where people are in

relevant-time serve three main functions (Figure 1):

Geofencing indicates whether an individual

has moved into an area where he or she does

not belong due to hazardous conditions,

inadequate training, or other issues.

Safety mustering lets first responders know

that people in the plant have moved to the

correct safe areas during a drill or actual

incident. If they are not in a safe area, the

system will alert users to their location.

Safety alerting allows a worker who is injured

to push a button on his or her wearable

location tag pendant to indicate an

emergency in progress and show responders

where to find the person.

These types of systems are not necessarily

new, but making them practical to install in an industrial

environment has been a challenge since no fully wireless

solution has been available. For example, knowing that a

worker is somewhere in Unit 2 might be adequate in some

cases. In other cases, responders may want to know if the

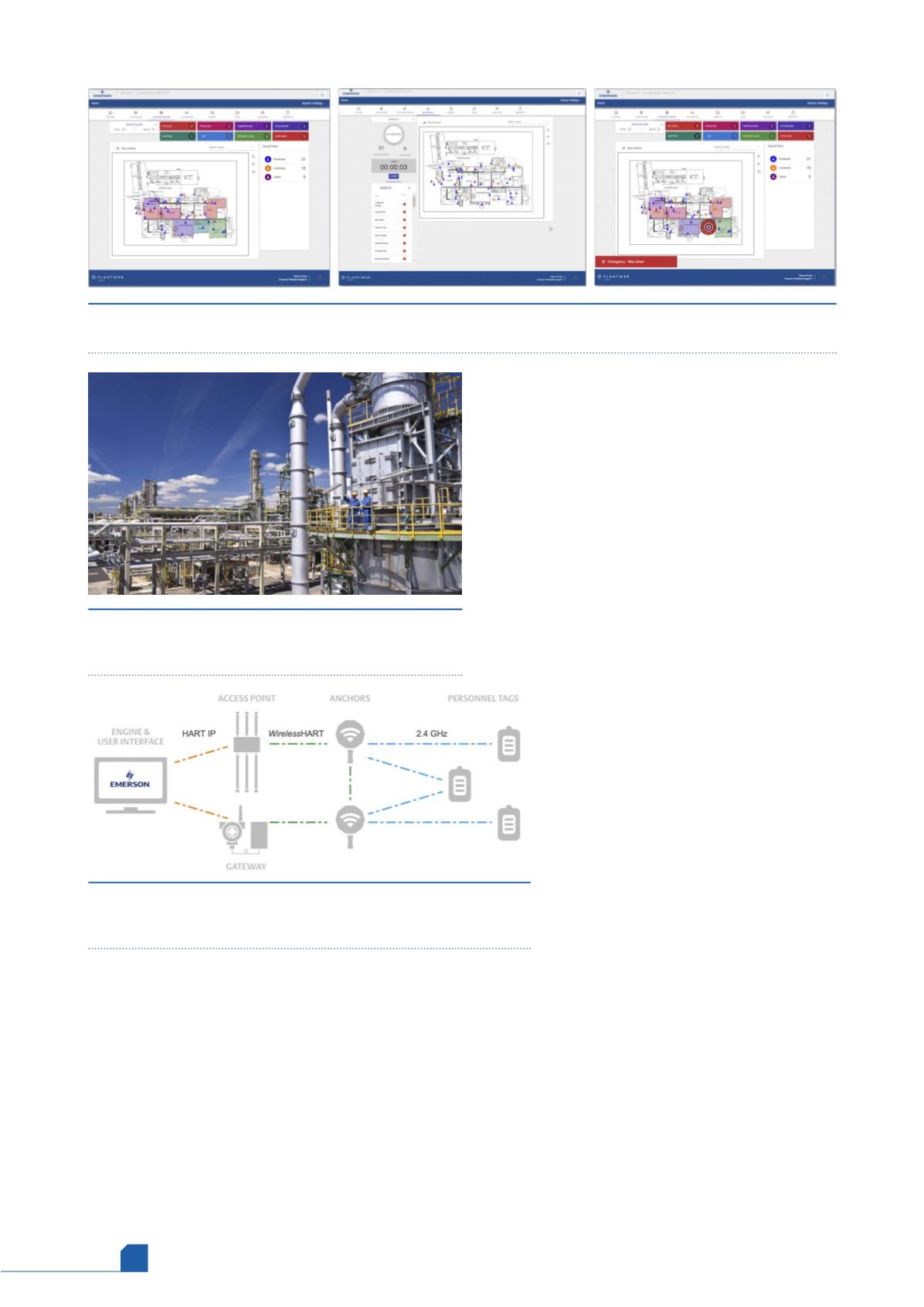

person is next to Surge Tank B. Process plants exist in three

dimensions (Figure 2) so height can often be a major factor,

which means receivers need to be placed at various levels.

Improving location resolution usually requires adding

Wi-Fi routers in more locations, but this is an expensive

proposition since industrial routers are costly, especially those

rated for hazardous areas, and must be hard-wired for power,

raising the installation cost substantially. Fortunately, there are

lower-cost options that are just as effective.

Figure 2.

Refineries and general process plants often

have many levels, so location systems have to consider

height.

Figure 3.

Individual personnel tags communicate with the anchors,

which in turn communicate with the WirelessHART gateways and

access points.

Figure 1.

Software designed to support location system functions can include pre-designed user graphics,

including geofencing (left), safety mustering (middle), and safety alerts (right).